Today’s bike comes from Buzz Kanter, the Editor-in-Chief of American Iron Magazine. Over to you, Buzz. I bought this bike in full street trim a few months before the Motorcycle Cannonball, but left it parked in secure storage. (I had to focus all my spare time on prepping my 1915 Harley for the cross country ride.) I purchased it from a bar owner who’d shut down his bar and was selling the classic motorcycles he had on display. He’d bought this Harley model J racer a decade or so earlier, and was told it was correct and complete. It wasn’t.

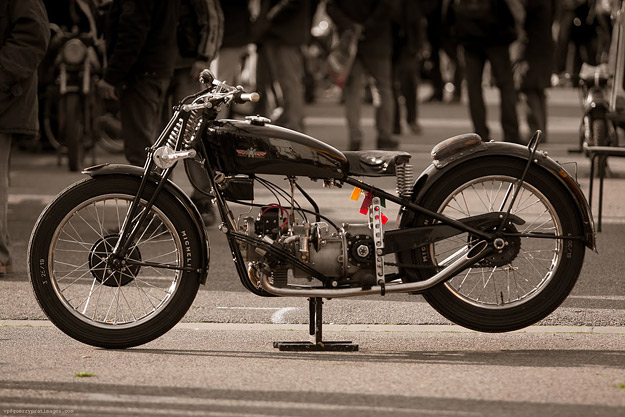

This 1926 Harley-Davidson features a front brake (Harley did not offer front brakes until 1928), home made exhaust headers and a British muffler, an export-only front stand, an accessory to hold a British tax disc on the stock tool box, and 1930s Harley VL gas tank decals. The ignition was a home made deal, with two coils hidden inside the battery box and a pair of externally mounted condensors. Harley would have used a single coil and condensor for this motorcycle. Close, but not correct all around.

I brought it down to Wheels Through Time to work on it with my friends Dale and Matt Walksler. After not running for more than a decade, Dale got it running in less than a half hour. We charged up a small 6-volt battery and took it for a short and smokey ride around the museum grounds.

Back in the workshop we pulled the old stock Schebler carb, cleaned it out and installed a newer 1930s Linkert bowl and new Rubber Ducky float to the 1920s Schebler carburetor. We changed out sparkplugs and took it out for a ride on the street. It ran OK but handled poorly, and was very twitchy on the road. I suspected the frame might have been bent.

Back to the workshop, where we discovered the steering head bearings were loose and dry. We jacked up the old Harley and removed the front end. Cleaned out what little grease was there—it might have been the original 1926 factory grease—and cleaned and inspected the races. They were OK, so we added fresh grease and reinstalled the loose balls and the front end. After that it handled great on the roads. We got it up to about 50 mph.

The next thing we did was pull the front wheel (it turned out to be a one-year-only 1929 Harley wheel and brake) and rebuilt the hub with new races, bearings and grease. The rear wheel was OK. We then greased all fittings everywhere on the bike; some were Alemite fittings, others were zerk.

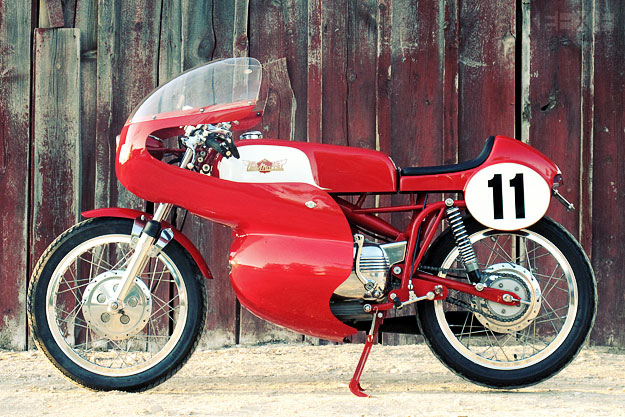

Once we had it running as dependable and strong as possible, we stripped it down as a priveteer racer. Off came the front fender, headlight, tool box, luggage rack, rear section of the rear fender, taillight, and more. If it wasn’t needed it came off. We took it out for a test ride and ran it hard for several miles. It handled great and looked right. Once back at the Wheels Through Time museum I carved out a set of race plates and hand fabricated mounting plates.

All this, from start to finish, took less than three days. It sure is nice to be able to work with guys like Dale and Matt Walksler, who know these bikes inside out AND have the spare parts on hand when needed.

American Iron Magazine will be running a full feature on this build (with more photos) in the Spring of 2012.